context

This is a paper i wrote for my Government course; it’s about current and imminent issues about AI and how local regulators should deal with them. It’s not as epistemically rigourous or entertaining as i’d normally shoot for for a blog post, but i figured i’d post it here anyway. It also doesn’t cover the extreme issues i care more about: existential risks from artificial superintelligent agents and the risk of astronomical amounts of suffering from conscious AI systems.

overview

The field of artificial intelligence (AI) has seen rapid advancements in recent years, forcing citizens and regulators alike to ponder what new rules should be implemented to ensure that the technology brings as much benefit to society, and as little harm, as possible. This report will provide an overview of how different state governments in the US are regulating AI, as well as the technical details necessary to understand the issues this rapidly evolving technology might cause.

Fundamentally, artificial intelligence refers to machines that possess the ability to reason, learn, and execute tasks that are typically performed by humans. In its early stages, these machines were manually programmed, and their creators focused on rule-based systems and expert knowledge. Over the years, the field has undergone two boom–bust cycles, with periods of rapid advancements followed by stagnation (“AI winters”). Today, it has transformed significantly with the advent of deep learning, a technique that involves iteratively updating the weights of a large neural network by exposing it to large amounts of data.

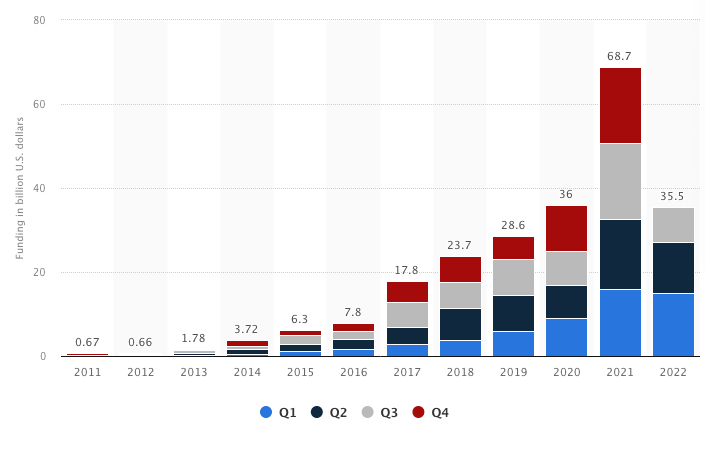

Deep learning has enabled AI systems to automatically perform a diverse array of impressive tasks that many used to think were impossible for a machine to do, from generating text, code, and images, to operating vehicles in real-world environments, to detecting and categorizing objects in photos. This has brought on a surge of interest in the field, creating a positive feedback loop of new capabilities and increased funding.

Funding of artificial intelligence in the US has been increasing exponentially over time.1

However, these novel capabilities bring with them novel legal challenges to consider: for example, how should states regulate companies who collect user data to train new AI models, or employers who use AI systems to choose which candidates to hire when those systems might have systematic biases? Potential issues, which will be expanded on in a later section, include

- Copyright of the data used to train AI models

- Privacy of the users who generate data

- Biases in models which reflect the data used to train them

- Reliability in safety-critical applications

- Interpretability of models

- Adversarial attacks

- Empowering rogue bad actors

- Displacement of jobs due to AI-enabled automation

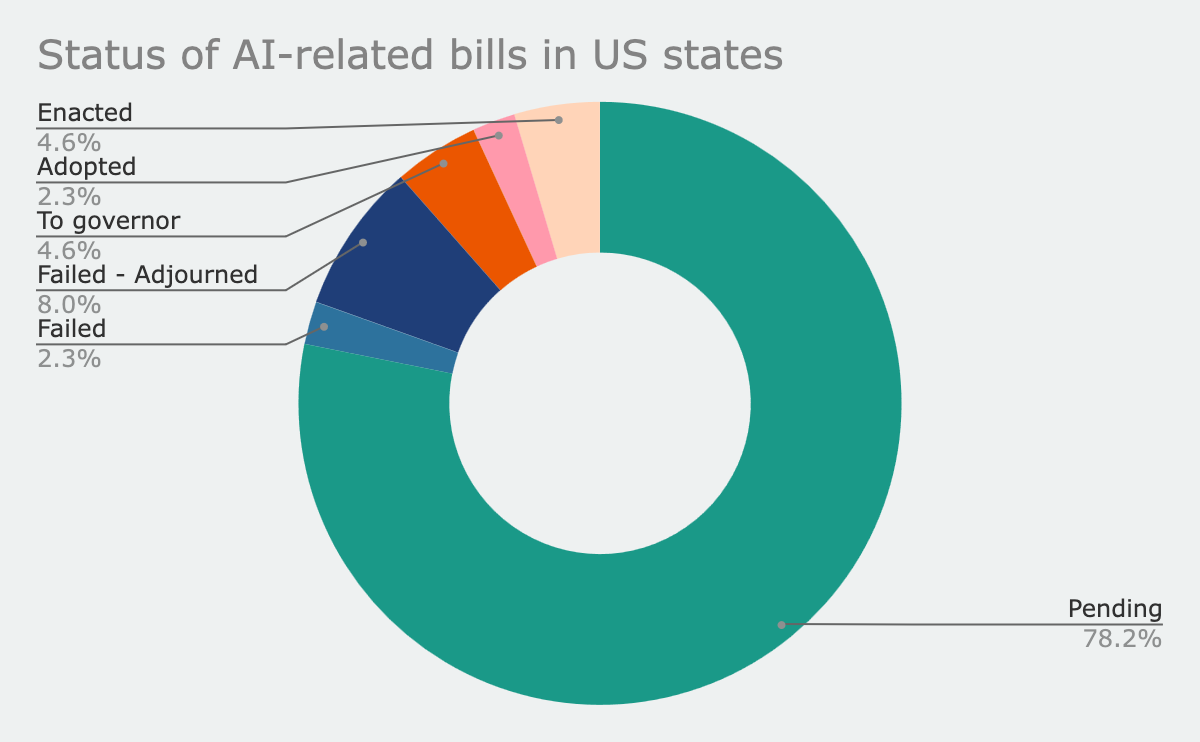

In its present state, the set of local regulations relating to artificial intelligence does not reflect this multitude of forthcoming, and current, issues. This is because the technology sector famously races faster than regulators can keep up with, and AI is no exception. As of May 2023, only four state bills have been enacted which relate to artificial intelligence:

- A Georgia bill which appropriates funds across a variety of sectors and includes a $65 million grant to expand AI manufacturing across the state

- A New Mexico bill which also appropriates funds and includes a grant for an academy charter school to purchase artificial intelligence equipment

- A North Dakota bill relating to the definition of personhood, which excludes (among other entities) artificial intelligence systems

- A West Virginia Bill creating a pilot program relating to the optimization of roads, which will use machine learning (ML) to assess them

With the exception of the North Dakota personhood bill, none of these local regulations address the most fundamental issues related to AI going forward. The vast majority of local regulations on AI are yet to come.

The vast majority of AI-related bills in the US are in the pending stage.

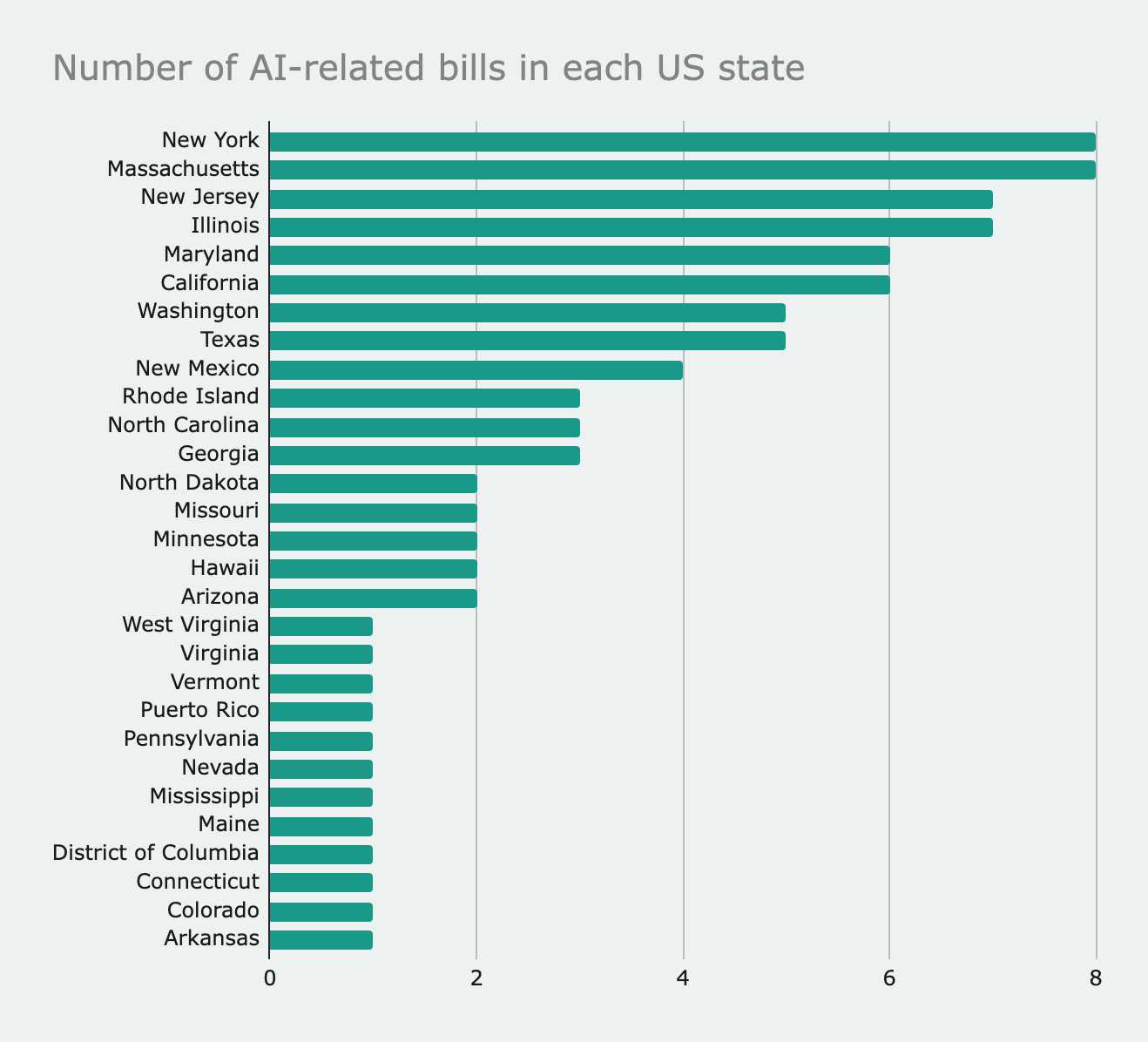

States such as New York and Massachusetts have or are considering the largest number of AI-related bills.

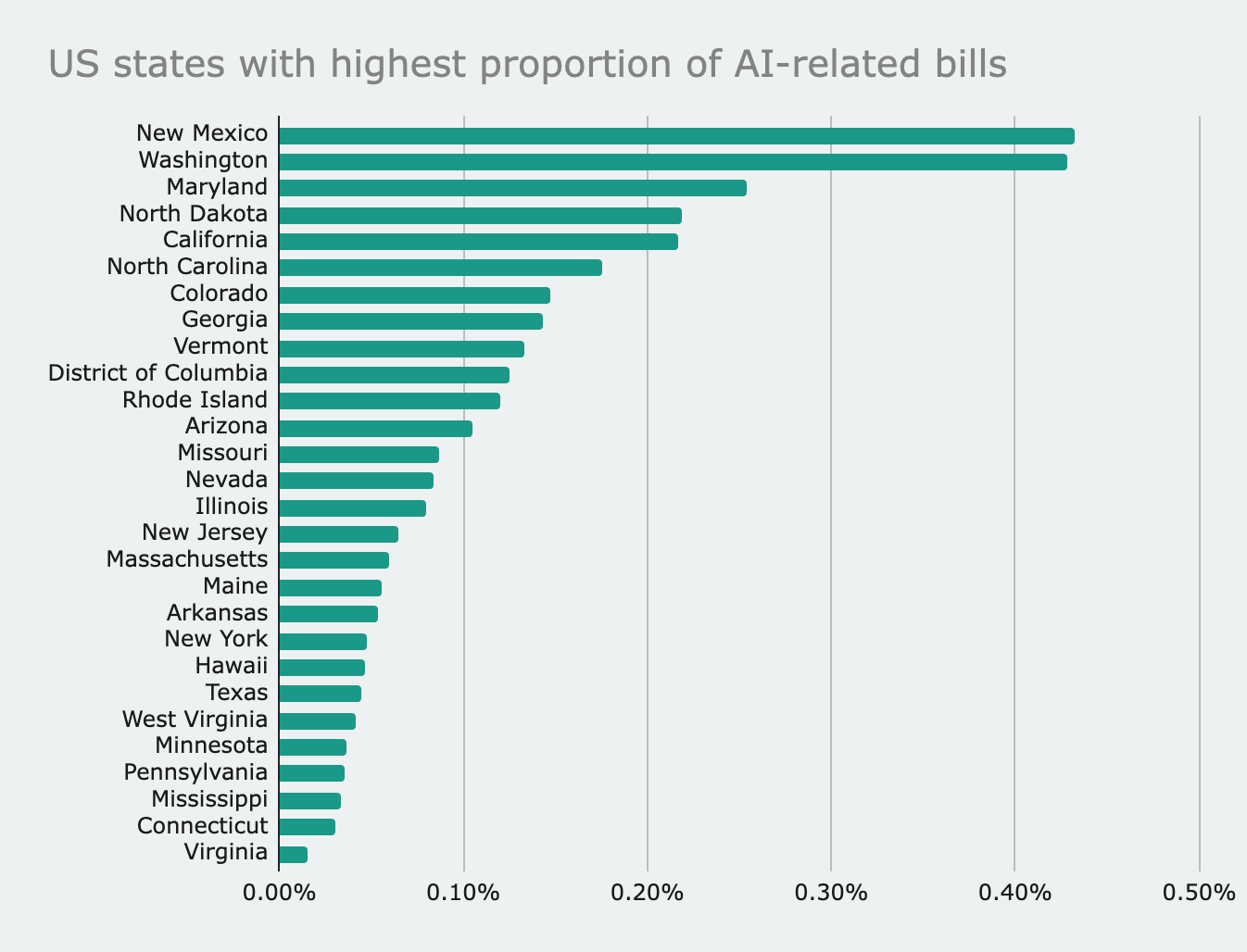

However, when the number of bills that a state considers overall is taken into account, New Mexico and Washington top the list as the most forward-thinking in this regard.

a diverse set of challenges

It is crucial to understand the basic nature of deep learning in order to reason about how to regulate the field going forward. Deep learning works by starting with a layered “blank slate” neural network, which is a collection of weighted variables connected in a way that roughly models the structure of biological brains. This network takes a set of numbers as input, passes them through a complicated series of functions governed by the weights, and returns a different set of numbers as output. During the training phase of the creation of an AI model, the model is taught which outputs it should produce when fed different inputs. For example, if a researcher wants to teach a machine learning model how to differentiate images of cats versus dogs, they will first convert each image into a set of numbers corresponding to the image’s pixel values and then show to the model each set as well as what animal the set corresponds to. With each image the model is shown, its weights are updated according to an algorithm known as gradient descent. This encodes the knowledge about what differentiates dogs and cats in the weights.

In short, modern machine learning models learn much in the same way that humans do: they begin with no knowledge or biases and are shown thousands of examples of the desired behavior. After the learning process, novel inputs can be fed into the model to produce corresponding outputs. This basic process can be used to create models which can do anything from predicting the stock market to recognizing faces to generating text, and having a basic understanding of this process helps us understand the AI-related issues that regulators face.

heaps of data: copyright, user privacy, and bias

Because modern AI systems are trained using examples of desired input and output, they require a lot of data to be trained. For example, the model powering ChatGPT was trained using 570 gigabytes of data obtained from books, blogs, Wikipedia, articles, and other writings on the internet.2 By the very nature of the process of collecting data to use for training, machine learning engineers cannot get permission from each of the millions of authors who produced the content making up the data. This was made clear to Stability AI – the company behind the AI art generator Stable Diffusion – after they faced backlash from the visual artists who created the millions of images that the company used to train their model.3

The more data a company has access to, the more powerful of a model it can create. This creates a strong financial incentive to collect more data from its users. However, many users don’t want companies to collect and store every bit of information they give to a service. Not only does it feel creepy, but data breaches also happen constantly, which expose private details from a company’s servers to the public.

Finally, because AI models learn from being shown examples from the data, they pick up the biases that it contains. For example, in 2018, Amazon developed a model to vet candidates who applied for roles at the company. Because it was trained on previous hiring patterns, the model was unfairly skewed in favor of male candidates. Amazon subsequently scrapped the model. Out of all the proposed AI-related state bills, regulations to prevent automated decision-making from being discriminatory are especially popular. New Jersey alone is considering three pending bills of this nature.4

inscrutable matrices: reliability, interpretability, and adversarial training

The structure of modern AI systems is different from that of hand-coded programs and human brains in such a way that makes them less interpretable, less reliable, and vulnerable to adversarial attacks.

Instead of programs written in plain English, they are inscrutable matrices trained on trillions of bytes of data. This makes it difficult to make guarantees about how often they will make mistakes. For example, despite the impressive capabilities of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, they’re still susceptible to what is called “hallucinations”, or making up facts and rationalizing them to the end user.

Because AI models work probabilistically, researchers cannot prove anything about the behavior of deep learning systems – they can only run tests. For safety-critical applications, this might not be acceptable. For example, one of the reasons we don’t see more self-driving cars on the road today is that the reliability of humans is hard to beat. In “Humans are very reliable agents”, Alyssa Vance writes:

…human drivers are ridiculously reliable. The US has around one traffic fatality per 100 million miles driven; if a human driver makes 100 decisions per mile, that gets you a worst-case reliability of ~1:10,000,000,000 or ~99.999999999%. That’s around five orders of magnitude better than a very good deep learning model…

This doesn’t mean that deep learning models are inherently less reliable than humans in all domains – humans are probabilistic too and suffer their own set of inconsistencies, like cognitive biases and poor reaction time. But for applications like self-driving cars, not all algorithms are at the desired level of reliability yet.

Another consequence of the structure of deep learning systems is that they are susceptible to adversarial attacks, which include what are known as data poisoning and evasion attacks. Data poisoning makes use of the fact that the performance of a model is dependent on the quality of the data it was trained on. If the data is user-generated, a malicious actor can “poison” it by injecting faulty data into the training set. One example of this is a backdoor attack, whereby poisoned data influences the model to act in a certain way when it is fed an input with a particular “trigger” (like an imperceptible defect in an image).5

In evasion attacks, a malicious actor alters an input in just the right way so that it bypasses a machine learning model meant to detect undesired content. For example, Christopher Back et al. discovered techniques to alter hateful Twitter posts to bypass hate speech detection algorithms without altering the semantic meaning of the posts.6

A computer vision model which detects stop signs is deceived by an adversarially modified stop sign (right). A specially crafted pattern placed over the stop sign tricks the model into believing the sign is 80% likely to be a sports ball.7

All digital systems are susceptible to errors and targeted hacking attacks, including AI systems. Looking ahead, local regulators should establish standards for the reliability and security of AI applications which could put at risk the private data and physical safety of millions of users. However, while it’s important that local regulators establish safety standards, they should be wary about imposing overbearing restrictions or not coordinating with regulators in other localities, since this risks slowing down the adoption of new AI technologies and consequently reducing the positive effect they will have on the locality’s economy. For example, two autonomous driving entrepreneurs share their struggles trying to expand their service to multiple cities in the US:8

Since the state and the federal governments had limited guidance on the deployment of autonomous driving services, we had to deal with each city individually to expand our operation, which is an inefficient and costly process given the regulatory differences among cities. In our cases in the U.S., the test data and safety assurance plans in California did not give us privileges when we applied for the test permit in Indiana. Although such an arrangement may be adequate to mitigate people’s safety risk in different states with different traffic densities, there could be room to improve process standardization and transparency, which would save AI start-ups’ resources and, in turn, help advance the technology.

emerging abilities: unpredictability, rogue actors, and job displacement

The final set of AI-related issues that regulators will have to confront has to do with the emerging capabilities of cutting-edge models. While these are the capabilities that will revolutionize society and potentially improve the welfare of billions, they’re also difficult to predict and can be harmful if they empower rogue parties with malicious intentions.

Compared to other technologies, the emerging capabilities of AI models are incredibly difficult to predict. The website Metaculus enables users to ask questions about the future and register their predictions about other users’ questions.9 According to a 2023 report, out of all categories of questions, the category which tended to result in the least accurate predictions (that is, the one which is most difficult to make predictions about) was artificial intelligence.10 Additionally, according to a paper from 2022 investigating the emerging capabilities of large language models as they are scaled up, these capabilities “cannot be predicted simply by extrapolating the performance of smaller models”.11

This means that regulators must think ahead. They cannot create laws based on the current capabilities of artificial intelligence and the harm it causes. Rather, they must proactively reason about what these models may be capable of in the future and create the necessary legal structures to prepare for them.

In 2020, Deepmind (an AI research group in Google) created the system AlphaFold, which predicts the three-dimensional structure of a folded protein based on its amino acid sequence. This system smashed the record in the bi-annual CASP contest, in which a hundred research groups from across the world compete to create the system which most accurately completes this task.12 This was a revolutionary feat in the field of computational biology, and it demonstrated how surprisingly powerful AI had become.

However, even though AlphaFold and advancements like it will help society develop better medicine, streamline transportation, and improve people’s quality of life overall, these new capabilities will cause harm when malicious actors have access to them. For example, anyone can automate the generation of misinformation to post on social media to influence the public’s opinions, and language models which can code will empower hacking groups to break the security of the companies and governments who can’t keep up. Roman Hauksson et al. demonstrated that language models can be trained to make more accurate guesses of people’s passwords based on information in their public social media profiles.13

The fundamental difference between AI and other potentially dangerous technologies is how accessible it is. Advancements in our understanding of nuclear engineering, for instance, have generally been kept safe because the procurement of materials used to physically manufacture nuclear bombs is highly visible and requires the coordination of different entities which are subject to regulation. In short, it hasn’t proved much of a challenge for governments to prevent individuals from producing nuclear bombs. Machine learning, however, is much more broadly useful than nuclear engineering, and the risks it might pose are less obvious, so more actors have been incentivized to research the field, and they have been more open about it, than nuclear engineering. There is a strong culture of open-access research in machine learning: almost every researcher uploads preprints of their papers to the open-access repository arXiv before they are peer-reviewed.14 This means that, unlike many other academic fields, potentially dangerous new applications are easily accessible.

A bad actor would have a hard time getting access to the necessary materials to construct a nuclear bomb. But the materials necessary to run most AI models are almost everywhere: computers. On February 23rd, 2023, Meta AI (Formerly Facebook AI) announced the development of a large language model called LLaMA and openly released the code they used to train it. Access to the weights defining the final trained model, which cost millions of dollars to produce, was granted on a case-by-case basis to researchers who applied. However, one week after the code was released, a researcher anonymously leaked the weights of the model for the public to download, enabling anyone to run it on their personal computers.15 This demonstrates how difficult it is to control the proliferation of artificial intelligence technology.

Local regulators have to account for the unpredictable nature of AI advancements as well as the difficulty in controlling access to them, but they will also have to take into account the effect it will have on the economy and particularly, the automation of labor.

A report from March of this year by OpenAI (the creators of ChatGPT) titled “GPTs are GPTs” claims that language models like GPT-3 (which stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer) are General-Purpose Technologies, meaning that they will affect the entire economy as opposed to individual sectors within it.16 Previous examples of GPTs include the steam engine, electricity, and information technology – these are innovations that increased the productivity of workers from a diverse set of fields. According to the report, “around 80% of the U.S. workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted.” Additionally, high-income, white-collar jobs are projected to see the most impact due to LLMs.

Local regulators should exert extra effort when creating laws regulating GPTs like AI because of their particular importance. The regulators may face pressure from local workers and unions to limit the proliferation of job automation technology due to the risk it poses to the workers it might displace, such as the truck drivers which self-driving trucks are expected to replace.17 However, localities that impose more restrictions on the automation of work in their area may not reap as many economic gains as those who embrace the changing labor landscape at the cost of short-term worker displacement. The general attitude among economists is that advancements in technology tend not to affect employment rates in the long term.18

conclusion

The field of artificial intelligence is rapidly evolving, offering humanity a plethora of new solutions. However, these emerging capabilities are difficult to predict ahead of time and bring with them risks from rogue actors. Like any digital technology, AI systems are also imperfect, in that they are not 100% reliable, they are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, and they pick up on the biases in the data used to train them. Unfortunately, while most US states are considering bills to address these issues, local regulators are still behind the curve. They should anticipate future advancements and risks from AI and preemptively enact laws to address them, while at the same time being careful not to stifle the economic and social benefits of increased automation.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/943151/ai-funding-worldwide-by-quarter/ ↩︎

https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrickcai/2022/09/07/stability-ai-funding-round-1-billion-valuation-stable-diffusion-text-to-image/?sh=76026a4124d6 ↩︎

https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/artificial-intelligence-2023-legislation ↩︎

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/JN6wm6u5MMmqwdnEs/metaculus-predictions-are-much-better-than-naive-base-rates ↩︎

https://github.com/ACM-Research/targeted-password-guesses ↩︎

https://ezramagazine.cornell.edu/FALL12/CoverStorySidebar2.html ↩︎

https://www.theverge.com/2023/3/8/23629362/meta-ai-language-model-llama-leak-online-misuse ↩︎

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160791X21002074 ↩︎